“A charismatic technology derives its power experientially and symbolically through the possibility or promise of action: what is important is not what the object is but how it invokes the imagination through what it promises to do.“

Megan Ames’s “The Charisma Machine: The Life, Death, and Legacy of One Laptop per Child” offers a compelling and critical examination of the ambitious One Laptop per Child (OLPC) initiative, a project that emerged from the MIT Media Lab in 2005. Championed by its charismatic leader, Nicholas Negroponte, OLPC represented a bold foray into the world of digital optimism, aiming to transform education in developing countries through the distribution of low-cost, rugged, and energy-efficient XO laptops. In her book, Ames explores the contrasts between the lofty ideals of this initiative and the stark realities of its implementation, providing insightful analysis and critique.

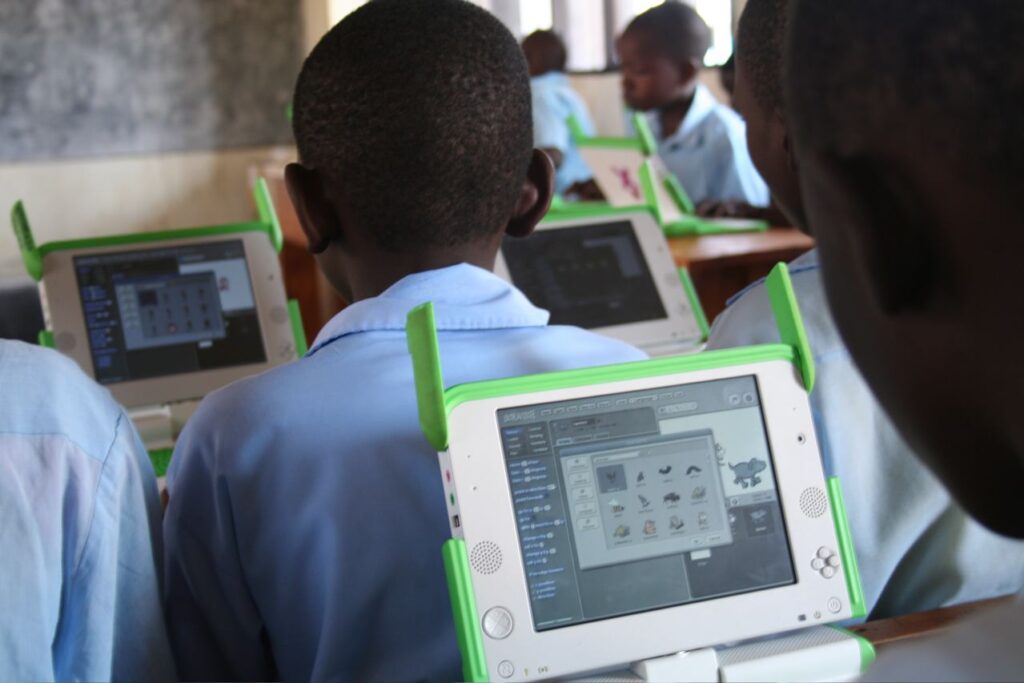

Ames’s book begins by setting the stage with the inception of OLPC, describing how the initiative was born out of a profound belief in the power of technology to democratize education. The XO laptop, with its distinctive green and white design, was a symbol of a larger vision to revolutionize education by providing children, irrespective of their socio-economic background, with tools to become proactive learners. However, as the story of OLPC unfolded, a chasm between this vision and the actual impact of the laptops on the ground began to be exposed.

As with many who lead development projects, Negroponte and OLPC’s other leaders and contributors wanted to transform the world—not only for what they believed would be for the better but, as we will see, in their own image.

The strength of The Charisma Machine lies in Ames’s thorough critique of the underlying assumptions and challenges of the OLPC initiative. She argues that while the project was fueled by a strong belief in the transformative power of technology, it fundamentally misunderstood the complexities of integrating technology into diverse educational and cultural landscapes and instead relied on charismatic technology. Her assessment extends beyond technological shortcomings, touching on the broader implications of tech-driven educational reforms, particularly in resource-limited environments.

It will be individual children who identify with the charisma of the XO laptop, and through the force of their inspiration, they will uplift their communities to the freedom and prosperity that OLPC promised.

Through her critical lens, Ames highlights the realities that confronted the XO laptop. She points out that despite its innovative design and intended functionality, the laptop’s actual use in various socio-economic settings often fell short of OLPC’s aspirations. The book emphasizes the delicate balance between technological innovation and the nuanced realities of educational ecosystems, underlining the necessity of a deeper understanding of effective technology integration in education.

The Charisma Machine further explores the broader context of technology in education. Ames sheds light on the significant role of external factors—such as family support, mentorship, and community involvement—in the effective use of technological tools. She further discusses the power of narratives and imaginaries in shaping perceptions about technology in education, illustrating how these can drive innovation and change but also create unrealistic expectations.

Even though there is something inherently unjust in accepting that only a few children may benefit from a charismatic technology—which children, under what circumstances, and with what effects on equity?—there is another element that is even more problematic. In particular, the project’s focus on student-led learning, drawing as it does on imaginaries such as the technically precocious boy, does not account for the critical role that various social worlds and institutions—including peers, families, schools, and communities—play in shaping a child’s educational motivations and technological practices.

OLPC’s journey, from a pioneering initiative to a more cautionary example, reflects the shift in how such projects are perceived over time, transitioning from beacons of hope and progress to reminders of the intricacies involved in implementing technological solutions in education. As Ames highlights, understanding the appeal of such visionary projects can help stakeholders identify, manage, and even exploit the narratives driving technological interventions without getting caught up in them. This insight is crucial for developing effective and sustainable educational technologies that align with the specific needs and contexts of the communities they aim to serve.

In retrospect, the OLPC story serves as a vital case study, encapsulating the intricate relationship between technology, education, and societal contexts. It underscores the need for technology to be adaptable and responsive to unique cultural, social, and infrastructural landscapes. The critique of OLPC also invites a deeper exploration into the promises and perils of technological utopianism in education, urging a nuanced understanding of the dynamics at play. The Charisma Machine offers a valuable lessons and insights regarding charismatic technology in EdTech or ICT4D projects, advocating for initiatives that are not only grounded in reality but also inclusive and transformative, fostering a future where technology in education transcends boundaries, promotes inclusivity, and amplifies the voices of all learners.

Reference

Ames, M. G. (2019). The charisma machine: The life, death, and legacy of One Laptop per Child. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. 328 pp