The Matthew effects in education refer to the compounding of academic advantages or disadvantages over time, creating increasingly significant disparities in educational achievement. This concept was coined by the sociologist Robert Merton. The “name”Matthew Effect” was named after a parable in the biblical book of Matthew: “For whoever has, to him more will be given, and he will have abundance; but whoever does not have, even what he has will be taken away from him.” (Matthew 13:12). The core of the Matthew Effect is its reinforcing nature: early successes result in additional opportunities and resources, perpetuating a cycle of advantage, whereas initial difficulties can lead to limited opportunities, further intensifying academic struggles. Comprehending this effect is vital for tackling the deep-rooted inequalities present in educational systems across the globe. (see Perc, 2014 and Walberg and Tsai, 1983)

The Matthew Effect: Origins

The Matthew Effect was initially used to explain situations where famous researchers continued to receive credit for notable discoveries and ideas, when in fact, lesser-known scientists had published findings on the same topic before them. But evidence of the Matthew Effect can be seen in every aspect life, from politics and religion to education. Rigney notes, “The study of Matthew effects is concerned with how inequalities persist and grow through time. It explores the mechanisms or processes through which inequalities, once they come into existence, become self-perpetuating and self-amplifying in the absence of intervention, widening the gap between those who have more and those who have less.”

Underpinning the Matthew Effect in education is the principle of cumulative advantage. This principle reveals how children start their education with inherent benefits —whether due to socioeconomic status, availability of educational resources, or early academic skills —frequently outpace their peers lacking such advantages. This phenomenon acts as an amplifier of initial disparities, casting a spotlight on the entrenched systemic inequalities within educational institutions. These early advantages often translate into long-term educational and professional successes, further widening the gap between different socio-economic groups.

Socioeconomic status plays a crucial role in the Matthew Effect. Children from wealthier families typically enjoy access to a broad spectrum of educational resources, including sophisticated learning environments, a variety of extracurricular programs, and advanced learning materials. These resources create a fertile ground for academic growth, substantially boosting their learning outcomes. On the other hand, children hailing from less affluent backgrounds often encounter a scarcity of these enriching experiences. This lack of access to key educational resources not only limits their immediate learning potential but also places long-term constraints on their educational development. This stark contrast between different economic backgrounds underscores the broader societal issues of income inequality and educational access.

The Matthew Effect extends its influence to the critical domains of literacy and numeracy skills acquired at an early age. Mastery of these foundational skills sets a trajectory that significantly influences future academic and career success. Children who successfully navigate these early educational milestones are more likely to experience ongoing academic achievements, whereas those who struggle with early literacy and numeracy often find themselves trapped in a persistent cycle of academic difficulties. These divergent educational pathways, stemming from the earliest stages of learning, accentuate the importance of quality early education in shaping life-long learning trajectories.

The societal impact of the Matthew Effect cannot be overstated. It perpetuates a cycle of educational and socio-economic inequality, where the disparities in academic achievement are closely mirrored in wider economic and social divisions (see Bask and Bask, 2015). This cumulative advantage or disadvantage effectively cements class structures, limiting the scope of social mobility and perpetuating existing societal hierarchies. Such an entrenched system poses significant challenges to the ideal of meritocracy and equal opportunity, calling for a critical reevaluation of educational policies and practices.

Technology’s Amplification of the Matthew Effect in Education

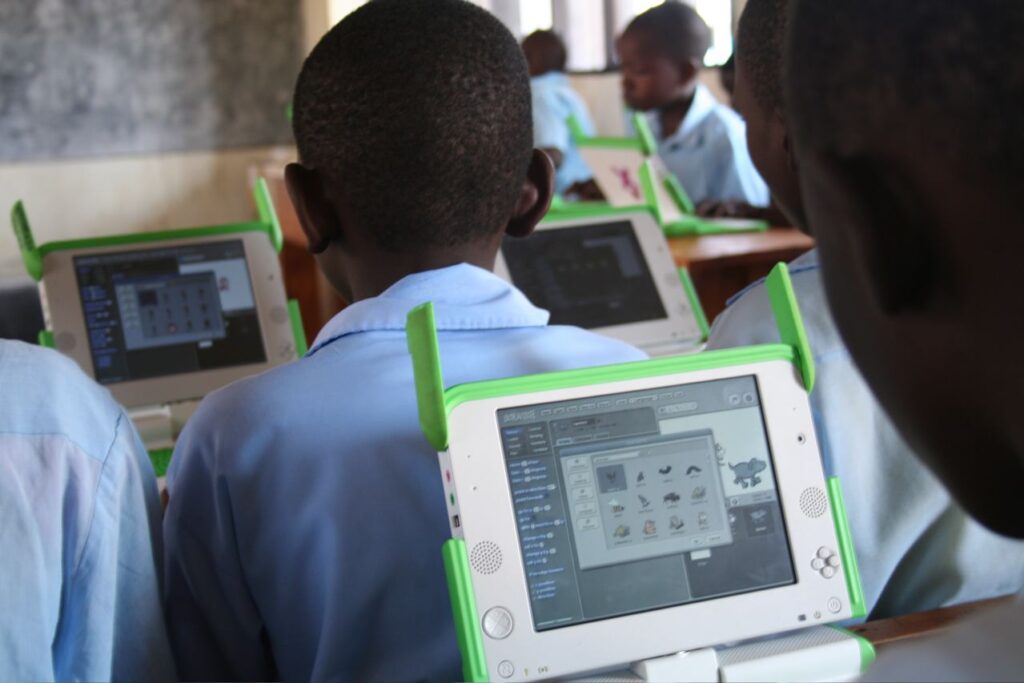

Educational technologies (or technology in general), while offering unprecedented opportunities for learning, have paradoxically also intensified the Matthew Effect. Technology, heralded as a great equalizer in education, often plays a contradictory role. Its potential to democratize education is significant, offering diverse learning tools and resources. However, the reality is more complex. The disparity in access to technology—often referred to as the digital divide—mirrors and magnifies the existing socioeconomic divides. Students from affluent families are more likely to have access to high-speed internet, personal learning devices, digital learning platforms, and the skills that go with it. In contrast, students from less privileged backgrounds may struggle with limited or no access to these technologies. This divide not only affects their ability to engage with digital learning materials but also limits their exposure to essential digital literacy skills.

Moreover, the rapid integration of technology in education requires a level of digital literacy that is not uniformly distributed across different socioeconomic strata. Children who are exposed to technology from an early age, often from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, are better equipped to navigate and leverage these tools for learning. Conversely, students with limited prior exposure to technology face a steep learning curve, hindering their ability to benefit equally from digital educational resources.

The pandemic-induced shift to online learning further highlighted how technology can amplify educational disparities. Students lacking reliable internet access or adequate devices found themselves at a significant disadvantage, unable to participate fully in remote learning. This situation not only affected their immediate learning experiences but also had long-term implications on their educational trajectory.

The effective use of technology in education should be accompanied by policies and practices aimed at minimizing these disparities. This includes ensuring equitable access to technology and digital literacy training for all students, regardless of their socioeconomic background.

Digital Divide as a Catalyst in the Matthew Effect in Education

The digital divide refers to the gap between those who have easy access to the internet and digital technologies, and those who do not. This divide is not just a matter of technological access; it encompasses differences in the ability to use and benefit from digital resources. In the context of the Matthew Effect in education, the digital divide acts as a catalyst, accelerating the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students.

Students who have access to digital tools and high-speed internet are better positioned to benefit from the wealth of educational resources available to them. They can supplement their learning with educational software, access vast digital libraries, and participate in online learning communities, and more important have the knowledge and skills to do so. This access enhances their learning experience, offering a broader and deeper educational engagement.

Conversely, students lacking such access and skills are doubly disadvantaged. Not only do they miss out on these additional learning resources, but they also face challenges in completing basic educational tasks that increasingly require digital tools. This gap in digital access and literacy leads to a divergence in educational achievement, reinforcing the patterns outlined by the Matthew Effect.

The digital divide also has implications for skill development critical for flourishing. Students with regular access to technology develop digital literacy skills almost as a byproduct of their daily interactions with digital devices. Those without such access lag in acquiring these essential skills, placing them at a further disadvantage in an increasingly digital world.

Learning and equity

Recognizing that the Matthew Effect can impact learning outcomes is perhaps the most critical first step to combatting the inequalities it creates. Matthew Effect contributes to systemic disparities between schools in underprivileged and affluent areas. Because schools in affluent areas can spend more money per pupil, they enjoy the best facilities, attract more experienced and competent teachers, and perform better in almost every aspect. Moreover, re-thinking the notion that talent is natural instead of nurtured is a significant step towards combatting the Matthew Effect and ensuring that learning is more equitable.

Furthermore, addressing the Matthew Effect requires a comprehensive approach. Interventions need to focus on equalizing opportunities, especially in early education, and providing continuous support throughout the educational journey for disadvantaged students. Furthermore, to effectively address the Matthew Effect in education, it is crucial to confront the digital divide. Solutions may include ensuring equitable access to technology in schools, providing affordable internet access in underserved communities, and integrating digital literacy into the curriculum. Without addressing the digital divide, efforts to mitigate the Matthew Effect will remain incomplete.

Reflecting on the Matthew Effect in education prompts consideration of broader philosophical and ethical issues. Ideally, education should serve as a tool for bridging social divides. However, the persistence of the Matthew Effect reveals the complexities in achieving this ideal. It calls for reevaluating societal values and structures that perpetuate educational disparities.

Further Reading

- Failure to Disrupt: Why Technology Alone Can’t Transform Education, 2022

- The Matthew effect: How advantage begets further advantage, February 23, 2010

- Overcoming The Matthew Effect In Early Education, March 9, 2018

- The Matthew Effect: What Post-Pandemic COVID-19 Readings?

- Educational Inequality in an Affluent Setting: An Exploration of Resources and Opportunity, Ronald L’Heureux Lewis, dissertation, 2008

- Merton RK. The Matthew effect in science: the reward and communication systems of science are considered. Science. 1968;159: 56–63.

- Carceral pedagogy

- Book Review: “The Charisma Machine”